The beauty of male love

sonder, essays; issue #2 — on 'The Last Dance,' Michael Jordan, and male love

Welcome back to sonder, essays! For the second essay of my new newsletter, I wrote about The Last Dance, Michael Jordan, LeBron James, the NBA, toxic masculinity, and most importantly, male love. This essay means a great deal to me. This essay is vulnerable, but I don’t break into my personal male relationships too much. I’ll be writing about my friends more in a future essay. I hope you enjoy this!

If you’d like to buy me a cup of coffee a month, please consider supporting on Patreon or sending me a few dollars on Venmo or PayPal. Every dollar is dearly appreciated. And of course, if you can’t, that’s totally okay! If you’d like to support me otherwise, drop a comment and let me know your thoughts on the essay, or share this newsletter with friends or family and consider asking them to subscribe.

Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson; Barcelona, Spain; Andrew D. Bernstein, NBAE/Getty Images

I recently watched the docuseries The Last Dance about Michael Jordan’s career through the lens of the Bulls’ final, legendary championship run of the 1997-1998 season. In the doc, there is a scene in where the mystique of Michael Jordan falls apart, at least to me.

The docuseries was two decades in the making and almost didn’t happen. When you watch it, especially in the midst of a pandemic where we’ve not had the drama of live sports in nearly six months, it’s strange to see two worlds long gone: The world of live sports and human connection and also the particular world of Michael Jordan and his Chicago Bulls. There’s something eerie about seeing photos and videos of the past; there’s a certain hue to old footage, it’s remarkable to see how people perceived the birth of a legend in real-time, and it’s especially cool to see moments of the past encapsulated in film, knowing the memories are embedded in their minds, in the film, and in the fabric of the universe. Sure, plenty of people alive today watched this god as he climbed the ladder to NBA GOAT-status, but his career and aura have been coated with two decades of new memories — and other subsequent basketball legends — that dampen this mystique from a blinding supernova to a fading, flickering bulb.

The fact that such footage even exists from the twilight of one of sports’ most notorious authoritarians is a miracle in and of itself. Unsurprisingly, and with the amount of control he had on that team, the footage taken during that final run was only publishable conditional upon Jordan’s consent. That’s why it took over two decades to reach the public eye. And even then, this is not exactly a critical look at Jordan’s career and reputation. With every single scandal that marked Jordan’s career, he’s given the opportunity to lead the narrative. For any sort of controversy, it’s only right that the person in the midst of it all should be given the opportunity to address it but that doesn’t change the fact that this is a swan song for Michael Jordan to control the legend around his name.

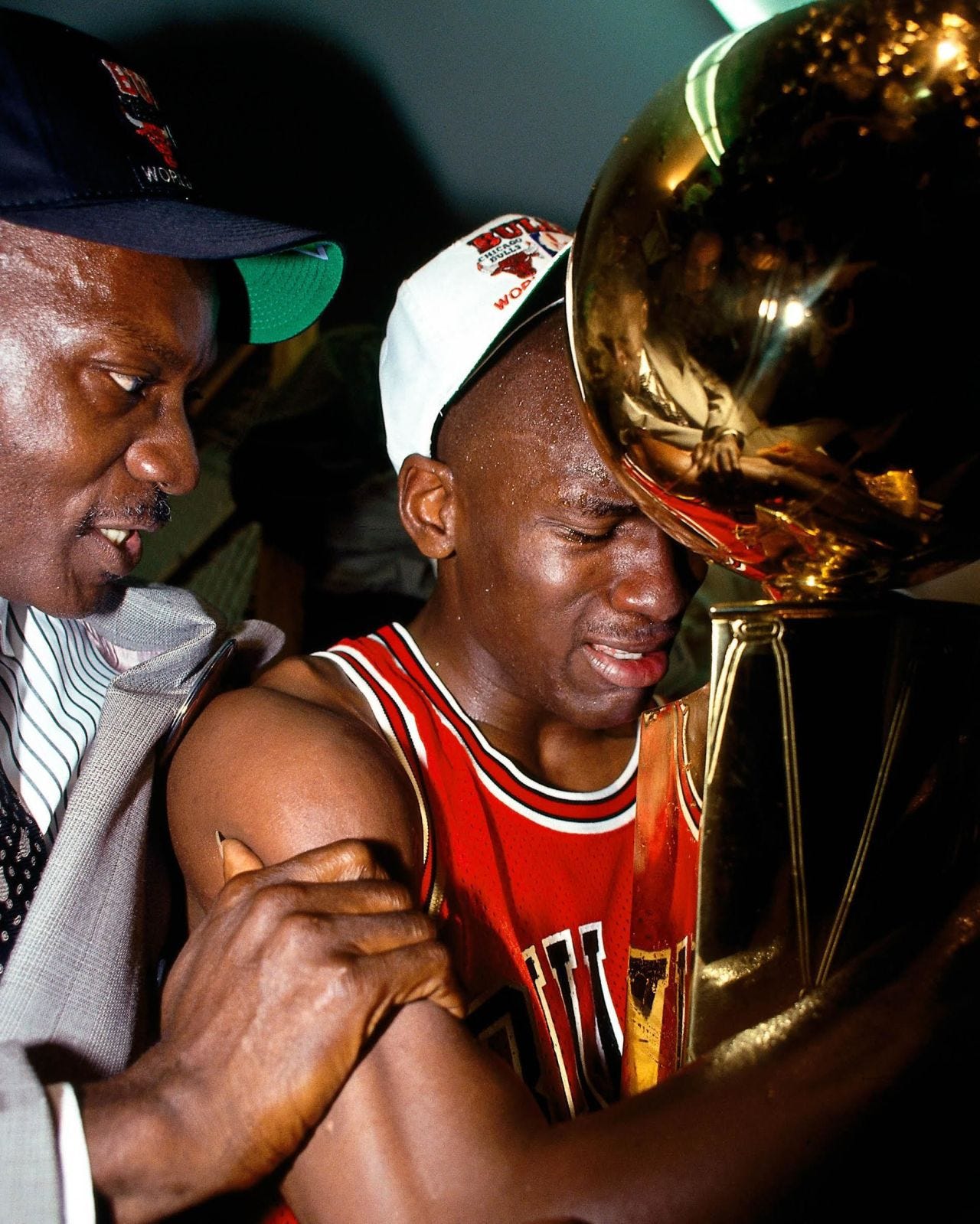

The contrast between the many versions of Michael Jordan — his college years, his early NBA years, his first championship run during the 1990-1991 season in his 7th season, his baseball days, his final championship run in his 13th season, and modern MJ — is fascinating by itself. We all transform throughout our life; this basketball player, like all other young athletes, did it under the intense scrutiny of the public and hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Not only did Michael Jordan have to grieve the tragic murder of his father (with whom he had a strong relationship), he had to field questions from the public about whether or not his father was murdered over his unpaid gambling debts. Not only a baffling, infuriating, and baseless accusation, but to pile that along with the incomprehensible grief of burying his father from a senseless act of violence, this young man was expected to handle the pressure of the entire world while inconsolably grieving.

It’s easy to dismiss these types of moments with little compassion; we can say there’s no reason to feel bad for arguably the most famous athlete of all time and (now) billionaire. That’s a pathetic and bland approach to evaluating a larger-than-life human being. There are plenty of criticisms to be levied against Michael Jordan; his treatment of his colleagues and teammates, especially the way he himself admitted to (somewhat unfairly) bullying GM Jerry Krause, his now-infamous quote “Republicans buy sneakers, too” after he was asked to endorse Black Democrat Harvey Gantt against incumbent outright racist Republican Jesse Helms for Senate in his home state of North Carolina, his inordinate gambling that many have long claimed (again, with no convincing concrete evidence) led him to be secretly suspended by David Stern which is why he abruptly “retired” in 1993 to play baseball. All of these criticisms are discussed in The Last Dance, both with many of the opposing parties and with Michael Jordan himself. As tyrannically as he was known to be, it shouldn’t come as a shock that MJ wanted to confront these stains on the record.

My first favorite movie of all time was Space Jam. I can remember falling in love with Michael Jordan; his charisma, his sense of humor, his passion, his insane talent, and his ability to conquer everything he wanted to conquer. Space Jam made sense with MJ’s ethos; it seemed legitimately possible that a man of his caliber — not just his basketball prowess, but his mindset that anything was possible with the right amount of dedication and confidence in one’s self — could actually defeat The Monstars. As I think back to my younger days, I recall admiring his compulsion to stand up in the midst of terrifying moments and not back down because of an adversary. Space Jam was another part of the MJ mystique; it solidified, for generations, millions of kids’ across the world lifelong belief that MJ was a god and could conquer anything. More than that, and as cheesy as it is, it made millions of kids want to believe in themselves and conquer those very unconquerable tasks. I mean this with utter sincerity: I track my love for Space Jam as a very young kid to the beliefs I hold today that we have to stand up for what’s right, not be intimidated by seemingly impossible odds, and fight even when we’re tired.

MJ and Bugs Bunny in Space Jam (1996)

Since getting older, MJ’s legend has faded just as LeBron James’s has become a supernova himself. Over the last two decades, since the day LeBron James entered the league (and maybe earlier), he has been compared to the ghosts of the NBA’s past, obviously most notably MJ. Much like MJ, LeBron James has been in the public eye from a young age and well into his adulthood. Not only have they both had to deal with public scrutiny as leaders in their cities and of their teams and organizations, but they are also Black men treated with even more scrutiny and more disapproval, especially by political figures. I have always greatly respected both of these men for their dominance on the court. They both, in different ways, find ways to win against any and all odds (and I strongly disavow the rings argument between the two for GOAT status). But pitting two legendary athletes who never played meaningful seasons in the same league against one another for individual title in a team sport is pointless; we can argue statistics between them all we want but it will never produce an answer that satisfies anybody.

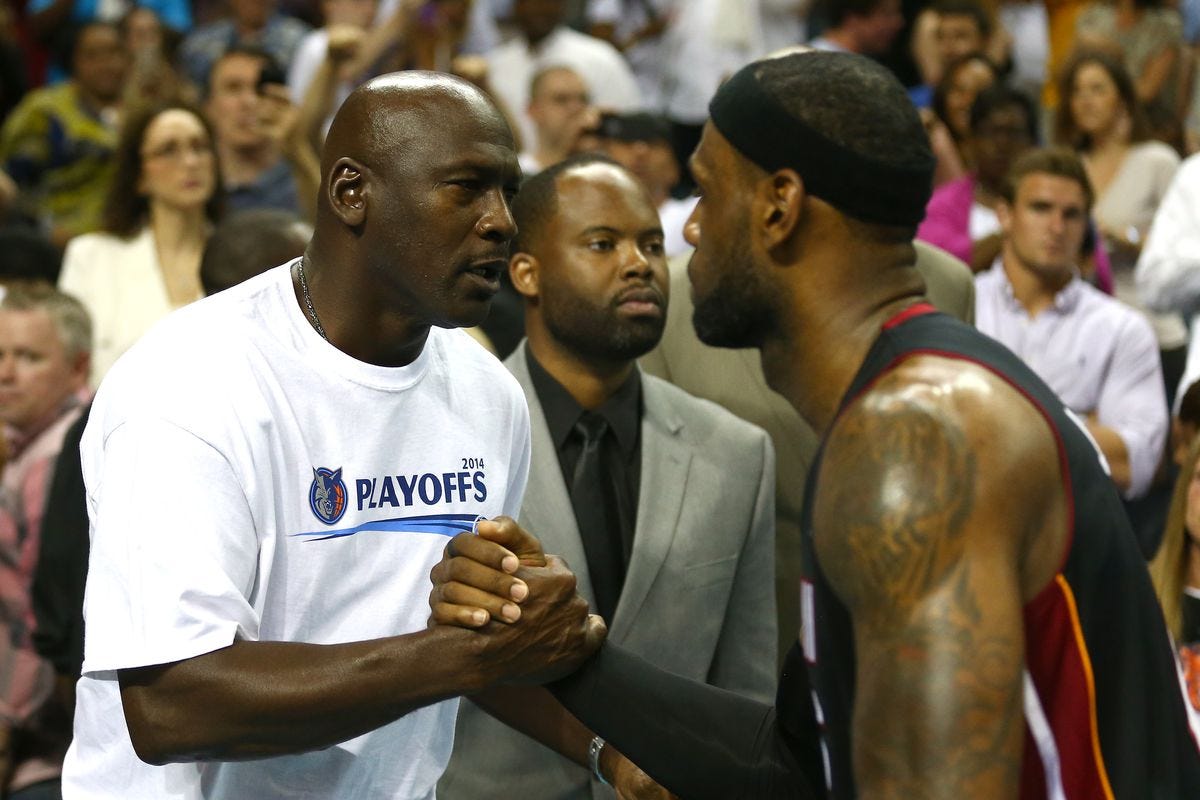

MJ and LeBron dapping one another up; Photo by Streeter Lecka/Getty Images

What I have respected so deeply about LeBron James transcends his time on the court; I have respected his public reputation and the care he puts into it to ensure that he doesn’t disappoint his millions of fans. I have respected his leadership on the court; it seems that his teammates and coaches respect him to his core and love him for the man he is. Mostly, I respect his leadership in the communities he lives in; he speaks out on critical issues (though I was disappointed with his apparent self-protective stance on the Hong Kong protests) and is willing to speak about political issues affecting the US while also criticizing leaders that are harming the majority of Americans. I greatly respect so many aspects of both of these men, and yet, in more ways than one, I disagree with both them and the pedestal which they have been placed on, mostly by no fault of their own. In the end, I don’t believe we should have dearly-held heroes that can eventually disappoint us. We must be our own heroes. That discussion is for a different day.

The scenes in The Last Dance where the mystique of Michael Jordan officially dissolved was not watching him get teary-eyed discussing his father’s murder or his relationship with security guard Gus Lett who filled a paternal role during the Bulls’ second three-peat or how his father never being able to watch him again is what partially inspired him to walk away the first time. Those moments are beautiful and meaningful and do tangentially relate to the pinnacle of The Last Dance, for me at least.

No, the scenes that meant the most to me were the scenes where Michael’s competitive aura dissipated after games or when joking around with other guys. It was the moments where I watched Michael Jordan, this relentless, singularly-focused superhuman caught up in the midst of affection for other men, his friends. These scenes — watching him joke around, tease, and dap up other larger-than-life figures such as Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, and John Stockton — made me realize something that contradicts the very thing Michael Jordan claims motivated him: It wasn’t personal.

The Last Dance is clearly not intended to be a story about manhood in America. But with any story related to a man in America, it will reflect what being a man in America is. Boys here are socialized to be “tough.” At a young age, we’re told we should be stoic and not display our emotions, either out of a misplaced sense of not revealing that we bleed too or out of a misplaced sense of displaying authority. We’re taught that winning matters and that being respected is more important than being loved and loving others. We’re taught that if we want something we have to go and get it. Manhood is a narrow standard we are expected to aspire to. We are not expected to do what’s best for us and our mental health but rather to do what is expected of us.

When I watched Michael Jordan joking around with, smiling, and hugging his guy friends (his boys) without the element of his legend attached, that, to me, was the most naked Michael Jordan ever was in The Last Dance. There is another beautiful moment when another basketball legend talks about Mike. Kobe Bryant mentions how early in his career, he was a young kid trying to navigate the pressures of being in the league while being undeveloped. He leaned on MJ for guidance. He goes on further to say, “I was the kid that shot a bunch of airballs, you know what I mean? And at that point Michael provided a lot of guidance for me. Like, I had a question about shooting his turnaround shot, so I asked him about it. And he gave me a great, detailed answer. But on top of that he said, ‘If you ever need anything, give me a call.’” This seems maybe not that important but consider this: The thread of that entire docuseries was that MJ was a cold-blooded killer who had no regard for anybody in his way yet he offered up advice and guidance to a player who modeled his own killer instincts after MJ. That’s a pretty special testament to his love and respect for Kobe.

It’s easy, or at least expected, that a man is going to be sad and cry about his deceased father; it’s entirely different for men to feel comfortable expressing their love for other men. When men and boys express their love, admiration, or even discontent with or to other men, they are brandished effeminate, homosexual, or sensitive. These terms, which are not negative terms to begin with — there is nothing wrong with effeminate, homosexual, or sensitive men — are used to berate and negatively stigmatize boys from a young age. When boys perpetuate these misunderstood concepts with one another, they are emotionally stunting one another; and as boys age without having these misconceptions corrected, they become men with these harmful notions about what is okay, what isn’t okay, and with an archaic belief about what being a man means. And when men with these destructive notions have children, they pass them along to their sons, daughters, nonbinary, intersex, and trans children. The term toxic masculinity is typically used to loosely describe the aforementioned phenomenon (Tolerance.org has a fantastic three-part series on toxic masculinity: part 1, part 2, and part 3).

I’ve always been a very sensitive person; as a boy, I was called fat in second grade and sobbed. As I got older, if my friends hung out together and I wasn’t explicitly invited, I felt that I was intentionally left out without rationalizing the many other likelier reasons for why I wasn’t invited. For a short time, I wondered if there was something wrong with me for being a sensitive boy; not by my parents’ fault at all but I wondered if I was failing to live up to my expected manhood even when I was young because I was sensitive, a term typically used for girls. As I grew older, I realized my sensitivity helped me a lot in life; it allowed me to navigate interpersonal relationships well, to be considerate of others, to understand how my actions impact others, and to try to learn how people could end up the way they were. My sensitive nature was driven by compassion for others and my compassion for others was driven by my desire to feel welcome in a world of pain, misery, and suffering, which was probably founded upon my fears from having a terminal disease. It can’t possibly be overstated how important it is to teach naturally sensitive boys to understand their love and compassion for others, no matter their gender or sexual orientation, is not something to be ashamed of. Even perpetuating sensitivity as a homosexual or effeminate trait is a homophobic and sexist notion.

My natural sensitivity left me blinded for a long time. I used to feel angry at other men who hadn’t developed higher emotional intelligence or developed the skills necessary to treat others with respect and recognize how their actions impacted others. This perception of vulnerability as weakness or that men are supposed to take every struggle in life on the chin is killing us and our brothers. The perceived weakness of vulnerability has led to men refusing to wear a mask during a global pandemic that has already killed more than 767,000 people worldwide (at the time of publishing). The emotions we feel are valid and they are necessary to recognize. We men have people in our lives that desperately love us and want us to be as healthy as possible. But we can’t solely rely on those others in our lives, especially the traditionally more emotionally intelligent women, to make us better and bear our burdens. We have to be better by taking responsibility and being accountable for our actions and our negligence. And to best perpetuate this, as we as men become better, we can continue to normalize this emotional metamorphosis. We can normalize being outwardly affectionate with our friends, crying as a means of processing our emotions, and going to see a therapist to better understand how to process our emotions in a healthy way. The way that I used to be frustrated with men for not being more emotionally-adept was a misdirected use of my sadness. Instead of being frustrated and expecting them to be culpable for the way they were raised in our society, I should have recognized their insecurities and their pain without outright dismissing their way of processing it. I should’ve been more inclined to reach out and do what I could to provide a loving space. And as I’ve gotten older and continue to better understand the pain that is repressed within other men, I do try to reach out and provide that space. We can’t prioritize demonizing struggling men; that will only push them down further. It’s difficult, but we must navigate a knife’s edge of asking men to be accountable for their own emotional maturity and how the lack thereof hurts others, while also providing a nurturing and loving space for them to grow.

With most of my friends and my father, I don’t feel the least bit of guilt or shame or insecurity when I hug them, tell them I love them, compliment them, or even constructively criticize them. For these relationships, I know there is a deep level of trust, respect, and love between us so even criticisms are usually well-taken as we both know it’s a matter of respect and helping one another be the best we can be. Platonic male love, once the husk of toxic masculinity is ripped off, is a beautiful, amazing, fulfilling phenomenon. It’s time we normalize this and create a culture that is better for men to comfortably convey their insecurities, their vulnerabilities, their loves, and their full selves. When we invalidate men and their emotions, we are continuing to tell them their emotions are invalid and therefore perpetuating emotionless men. This is obviously bad for men, but it’s also bad for male relationships with women, and it also perpetuates horrible stereotypes about gay men, trans people, and other communities within the LGBTQ+ space. We live in a patriarchal society. That part isn’t debatable. But the continuation of the patriarchy drives this continued socialization of men to be vicious, unemotional, authoritarian “leaders.” Though this seems paradoxical, the patriarchy is bad for men.

To build a better world, we must recognize our shared bonds. We must recognize what it means to be a loving, inclusive, welcoming society. The more we try to keep others from being welcome or felt included, the more we are building a world that will not reciprocate to us. That means we men have to strive for a better world for our brothers by broadening the definition for what it means to be a man — and that means recognizing that toxic masculinity is repressive and destructive for ourselves, for our loved ones, our society, and the world.

When I saw Michael Jordan dap his boys up, or cry in the arms of his teammates, I saw a man that loved winning and also loved his peers. His tyrannical tendencies were, at their core, insecurities. He was the best player on the court. The thing is, he never doubted he was the best on the court; he always believed in his core that he was the best to ever do it. What drove him was the insecurity that others did not see it that way, and his drive to win was to shut those who denied him his self-perceived greatness up. He used traditional masculinity — berating, making fun of, and tearing down his teammates — as a way to build them up, a style I believe strongly against. But this isn’t about that part of Michael Jordan; it’s about the part of him that loved the men he competed both with and against and he loved them in the beautiful way that men love each other when they’ve developed bonds strong enough to dismiss the social stigma that comes with showing that love. There comes a time when that love is so strong, so transcendent, that social stigma no longer means a thing. That’s the love we should strive for with one another, no matter their gender identity or sexual orientation. That’s the male love that I love and feel towards the men in my life that have helped me grow and weather the many storms life has thrown my way.

tré

Thanks for reading the second issue of sonder, essays! I hope you enjoyed it. I haven’t decided what exactly I’ll be writing about for the next issue but if you have some thoughts, please be sure to let me know in the comments, in a reply to the email, or any other way. I’m always looking for topic to write about and welcome feedback. Please let me know! And don’t forget to share this essay and my newsletter; that’s the best way to support my writing!

Click here to add all future issues of sonder, essays to your calendar!