They say it's all about the journey.

But what about when that journey has been full of potholes?

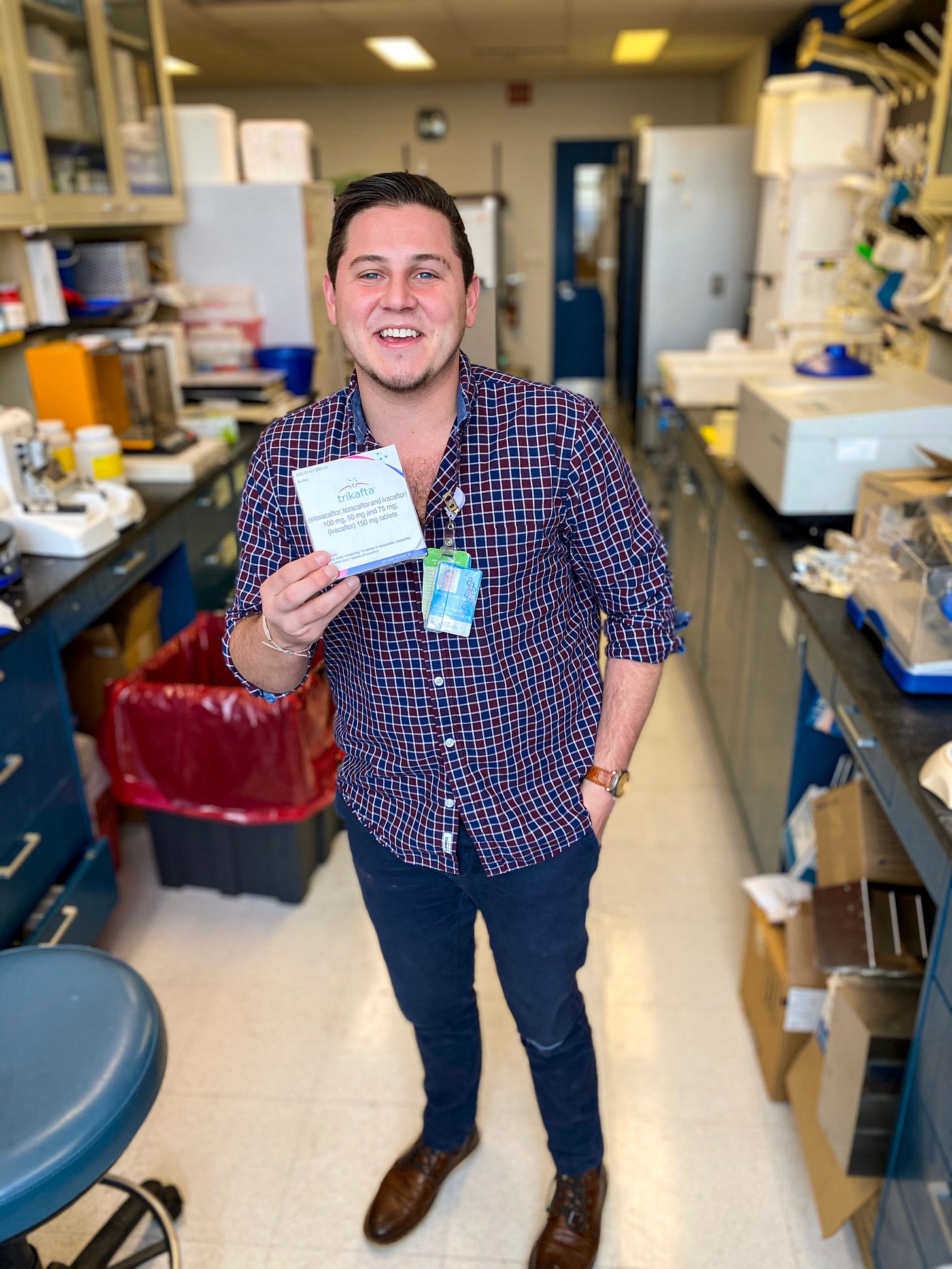

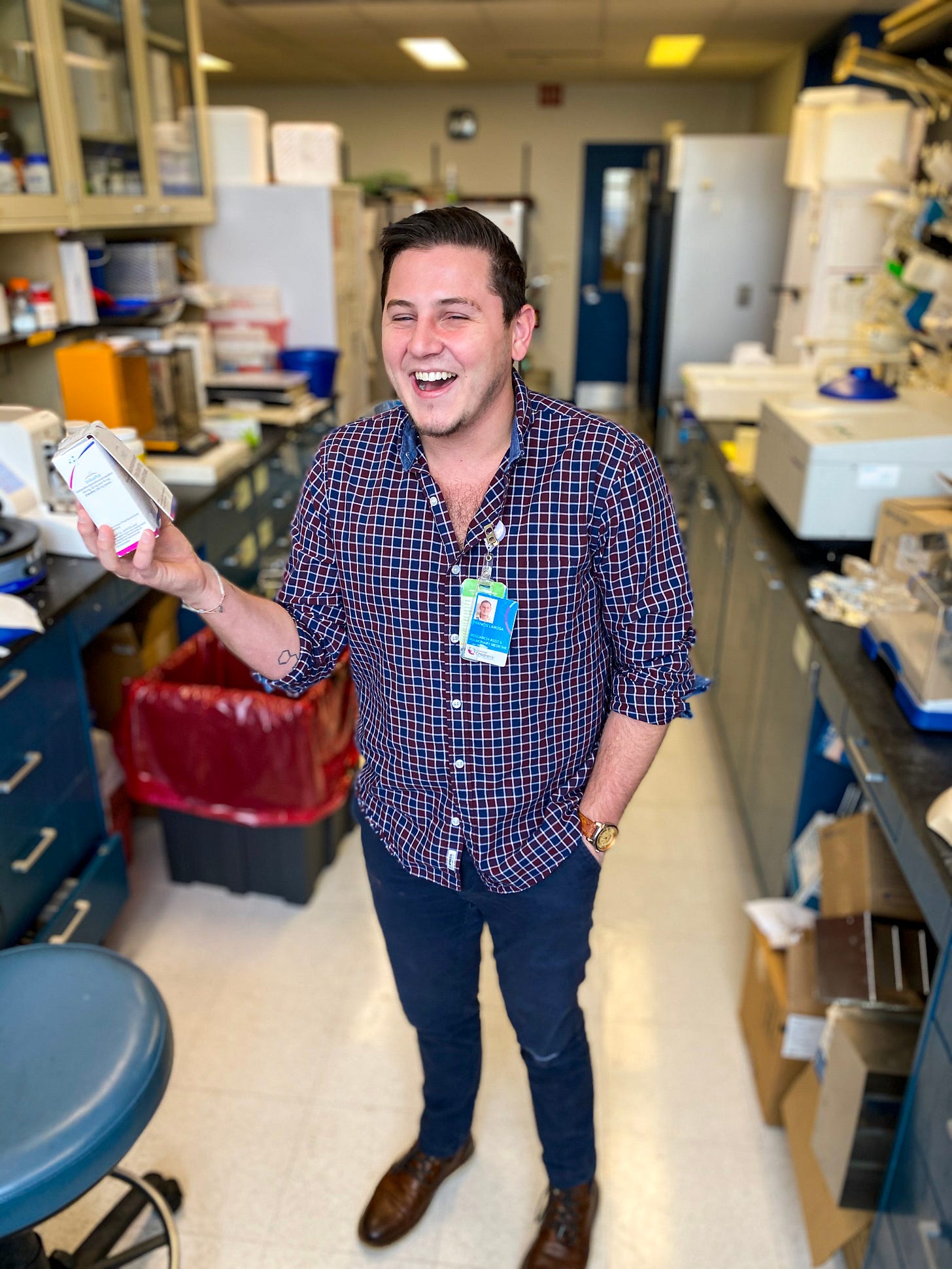

My life is supposed to change today. A bit over an hour ago, I took my first dose of the new cystic fibrosis therapy called Trikafta. I wrote about the complicated emotions that come with this groundbreaking drug on my blog. I’m proud of that piece and I think it explores the depth and nuance of these emotions in a strong way. It celebrates the achievement that Trikafta is while acknowledging how much there is to go and all that’s been lost along the way. It’d mean a lot to me if you read it.

My favorite part of that piece is the following excerpt:

And it’s a tremendous win. There is no other way around it: The combination of fundraising, advocacy, medicine, science, and common humanity over the past half century has led us to this moment. It is nothing short of a miracle of superhuman proportions. The victory is built on the backs of hundreds of thousands of people. The victory is also built on a graveyard. When CF is one day cured or at the very least not any different from a diagnosis like diabetes, it will come with the knowing that tens of thousands of young people died without a chance of a full life. They died after a short life where they underwent more physical and emotional trauma than the majority of people will sustain in their two or three times longer lives. Millions of people have grieved the demise of a loved one with cystic fibrosis.

Life is supposed to be all about the journey. It’s not supposed to be about the beginning or the end; our birth or our death; the starting point or the destination. It’s about how we get wherever we’re going. But how do we celebrate that if the journey, the road, the path is paved with trauma, devastation, and grief?

Years ago, a compound called Kalydeco was approved for a small subset of people with CF. For these people, life changed dramatically. Their mucus thinned, they cleared infections more quickly, they breathed more easily. A few years after, a new drug followed: Orkambi. The results for Orkambi were muted. Lives didn’t change, but maybe they stabilized a bit. Expectations became forever moderated. Trikafta is a different beast. This drug is changing lives already, presenting people with the hope for stabilized health and re-invigorated bodies and spirits. When your journey has been full of setbacks, constant health interruptions, needle sticks, anxiety, depression, antibiotics, stomach pain, strained breaths, and the specter of early death, what happens when you’re suddenly presented with…normalcy?

It’s hard to know what the long term effects of Trikafta will be. We must be cautious with our optimism and we must be honest about the possibilities. Maybe our lung function will only be stabilized for a few years, followed by the same decline that many of us have already begun to undergo. It’s difficult to predict. But our roads, already built upon fragile expectations, will continue forward, unpaved, then paved, then unpaved.

Since Trikafta was approved less than a month ago, I have looked at my future differently. As a scientist, I’d like to believe I’m realistic, but I have found myself full of a joy and optimism I’ve not known since long before my sister died. I have long feared a decline like my sister’s. I have started to think decades into the future, I have started to think of all the hundreds and hundreds of things I want to do with a life of stable health. My health has been stable for years, and yet, the opportunity of a reinvigorated life with fewer concerns have made me think the world is brighter, more beautiful, more conquerable than it has ever been.

It has been a hair longer than a year and eight months since my sister died a young, tragic death. When she died, I was scared; scared that I would wake up in perpetuity with a feeling of unfillable loneliness, emptiness, and weakness. My sister’s life was vibrant and she touched thousands of lives, but her story is pockmarked less by things she did, and more by things she didn’t. Alyssa would’ve traded her platform of inspiration for the chance to move out, to have common concerns like bills and buying a house, to get married, to raise kids, to work and then retire. Alyssa’s greatest desire was a life free of serious health concerns and full of “normal” worries. The greatest tragedy of my sister’s life is that she never had that chance.

Her story is the status quo in the CF community. People across the country — across the world — have health issues that force them to confront mortality early on. These health issues hijack their autonomy, break them down, and force them to build their personality and spirits on their health issues only to one day maybe supersede them.

When I reflect on my sister’s life — and also on the others I’ve lost along the way through varying degrees of tragic deaths, such as my Nanna’s abrupt death by metastatic liver cancer, or my Nonno’s agonizing mesothelioma, or my Granny’s long decline with heart disease and dementia, or our Yorkie’s sudden death by too much anesthesia — it’s hard not to feel like their lives are nothing but two points: Their births, when I wasn’t present, and their deaths, where I was present for almost all of them. To think I’ve seen three of the most important people in my world take their final breaths is to realize that I’ve been formed by the tragic deaths in my life. To think that my life has been characterized by health concerns, hospitalizations, depression, anxiety, and a morbid fixation with death for twenty-six years, only for it to now appear more open and free than it ever has.

I have many, many feelings about beginning Trikafta today. I want every person with CF — my idealistic side says every person — to feel this sense of hope. I’ve never known this feeling before. I plan on trying to give an honest assessment of what life with CF, while on Trikafta, looks like. I expect it to be complicated and fun and unexpected and scary and vibrant and beautiful.

I wouldn’t have it any other way. After all, they say life is all about the journey, right?

TL