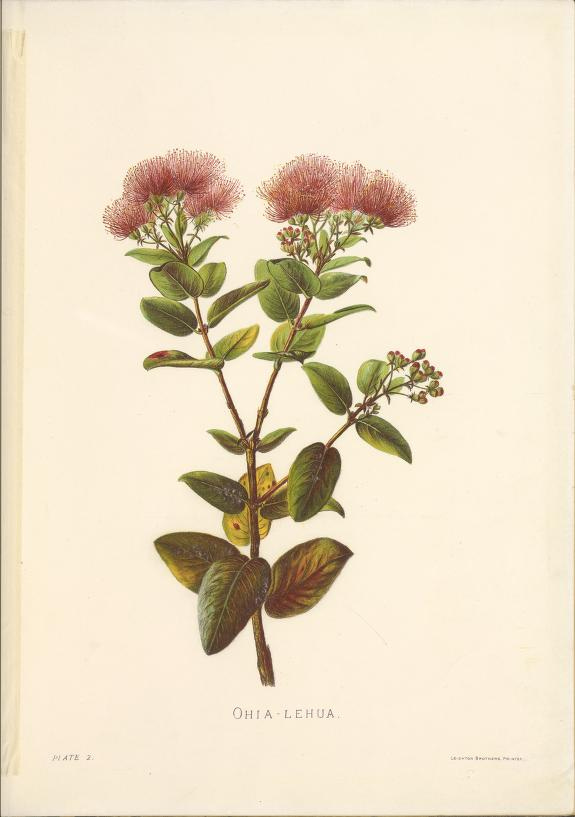

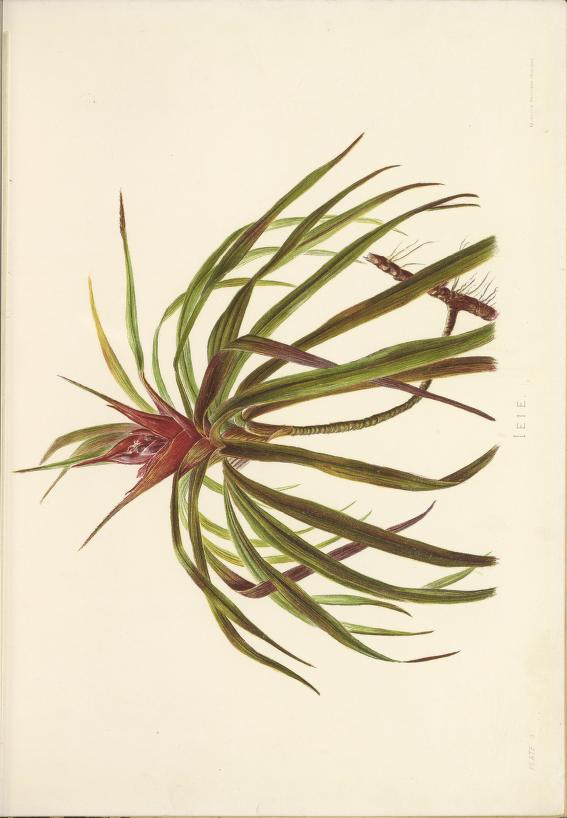

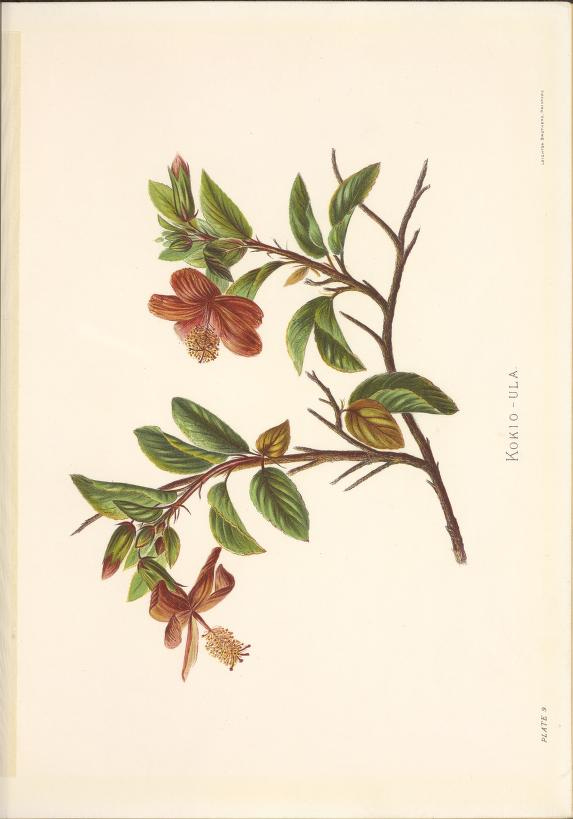

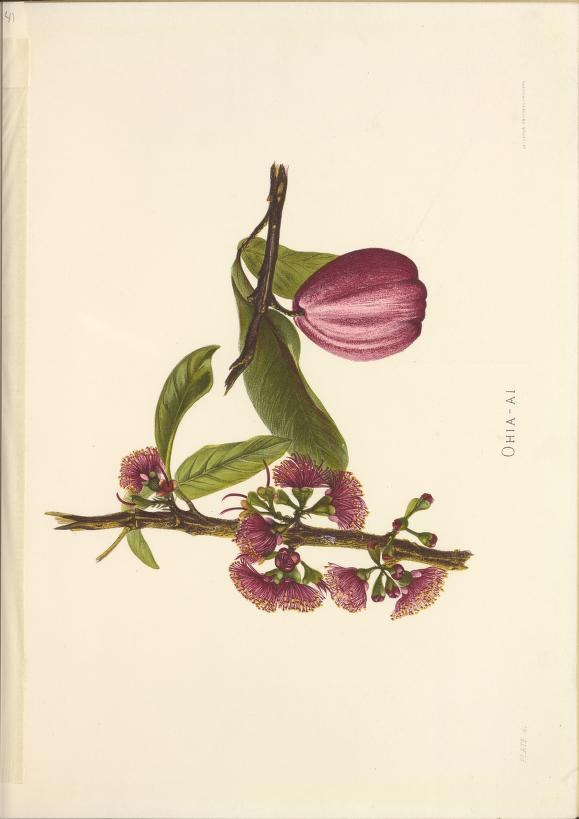

Life can be really difficult. We need to learn how to accept the hardships of life while believing the world can be better. We have to teach ourselves how to believe a better world is possible. Here’s my case for hope. All images in this issue are open-source from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. These images are sketchings of the indigenous flowers of Hawaii.

I hate doing this, but I don’t get any compensation for writing this newsletter, so if you’d like to support my writing, consider becoming a Patron on Patreon for $3/month. Each newsletter is written in my spare time and they each take a few hours to put together. I hope to make a few extra bucks here and there to keep this up and commit more time to my writing and see where that takes me. If instead of a monthly contribution, you’d like to drop a dollar or two as a tip, here’s my Venmo or PayPal. Every dollar is dearly appreciated. And, as always: feedback, email replies, comments, and shares are also dearly appreciated. I received a few tips and Patreon subscribers after the previous two newsletters. It made me tear up. To have people support my writing in that way is one of the coolest feelings ever. Thank you all.

As kids, we’re starry-eyed. We see the world through rosy tints and blue skies all the time. We’re intuitively optimistic and present in each passing moment. It’s hard to say if that’s due to our youth; we haven’t become jaded by the darkness of the world or the monotony of everyday life quite yet. Or is it due to naïveté? Youth and naïveté go hand-in-hand, I suppose.

It’s easy for us to become skeptical of the world. As we grow older, cynicism—no longer optimism—is the norm. We become less fascinated with the beauty of the world or with the hope of a better day, instead spending our time bored or frustrated, waxing poetic on years-long behind us while not making an effort or having the energy to improve our station. We default to the negatives of life and the expectation that life will only get worse and we’ll never again get a chance to feel joy again.

I’m not sure it has to be this way. We accept cynicism and deride others for their optimism. We tell them it’s okay to be jaded by the world and we tell ourselves that we hope for the best but expect the worst; in essence, pretend to be optimistic but be pessimistic. We call this “realistic,” as if “realistic” is the perfect middle ground. I don’t believe this is right. I find that realism is often just a different shade of pessimism. Of course life can’t always be perfect! Does anybody really think it will be? Even the most hopeful optimists are aware that life will never go perfectly according to plan. Optimism, much like compassion, is a skill. Pessimism, much like hate, is a by-product of a narrow–minded worldview.

We have to believe a better world is possible. And it’s up to us to get our minds there.

We can find beauty in just about anything. Cystic fibrosis is beautiful; there’s remarkable beauty in that while a microscopic protein can wreak such havoc on a community, the community has unspeakable solidarity. There are many disagreements in the CF community, but those disagreements are resoundingly present only because we all want our lives to be improved. We just disagree on the best path, but that the destination is the same is beautiful. CF sucks, there’s no disagreement there. I don’t think anybody will try to argue otherwise, but this is where pessimism and optimism come in. We can focus on the tragedies or we can focus on the wins and the community and the love that our solidarity engenders; we can be hopeful, if we allow ourselves to be. I’ve spent a lot of time pissed off knowing Alyssa’s life would’ve been much better if she never had CF, or with modulators, or if she had lived long enough to see a cure. But I’ve also felt a deep sense of belonging because of the love I’ve shared with so many that almost certainly wouldn’t have existed without us having cystic fibrosis.

It is up to us to re-frame our perspectives on the world. We can’t allow for pessimism — a belief that the world cannot be better — to destroy us. Pessimism, or a negative worldview, is a parasite; it is a cancer in our minds. It grows and multiplies and eats away and tears us down. It will allow for hate to flourish and discontentment to remain; pessimism will ruin our lives more than failure ever could. When we’re pessimistic, we assume failure is more likely than success, so we fail before we even make an attempt. Optimism, on the other hand, doesn’t mean that we’re definitely going to succeed. Optimism isn’t necessarily the opposite of pessimism; with pessimism, we say “I don’t think I’d succeed at that,” which creates a subconscious and conscious predisposition for failure. Optimism is more like: “I’m going to give this a try and if I succeed, great! And if I don’t, well I can become better.” This is why it’s important that we practice this re-framing. We can use this strategy for almost everything.

Optimism isn’t saccharine or toxic positivity. It’s recognizing that everything in life is an opportunity to learn and to grow and to become better and figure things out. Life won’t always be perfect; optimists, realists, pessimists can all agree about that.

The first step to a better world is believing it’s possible. I promise you it’s possible.

Thanks for reading, everybody. I’m so sincerely thankful. A quick author’s note: I don’t endorse the notion that positive thinking is the cure to depression or anxiety. But I do believe beating depression and anxiety requires a multi-faceted approach and one of the core parts of that is learning how to re-train our brain to look at things differently and combating the negative cascades caused by our depressed/anxious brains. Let me know your thoughts on this topic!

tl